ArtsVanGogh.com

Vincent van Gogh 1853-1890

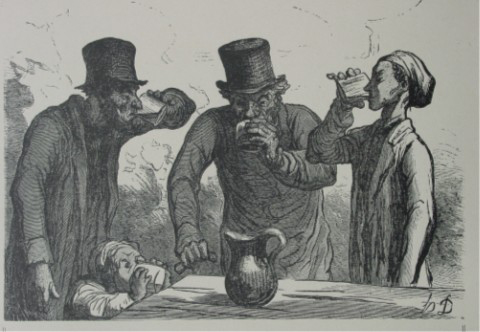

Vincent van Gogh - The Drinkers after Honoré Daumier 1890

/116 The Drinkers.jpg) The Drinkers after Honoré Daumier |

The Four Ages of a Drinker

Honoré Daumier

In 1882 Van Gogh had remarked that he found Honoré Daumier's The Four Ages of a Drinker both beautiful and soulful.

Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo : "What impressed me so much at the time was something so stout and manly in Daumier's conception, something that made me think It must be good to think and to feel like that and to overlook or ignore a multitude of things and to concentrate on what makes us sit up and think and what touches us as human beings more directly and personally than meadows or clouds."

From The Art Institute of Chicago:

During his time in the Asylum of Saint-Paul in Saint-Rémy, a small town near Arles, Vincent van Gogh made a number of copies of the work of artists he admired, which freed him from having to produce original compositions and allowed him to concentrate instead on interpretation. For this image, Van Gogh copied a wood engraving from Honoré Daumier’s Drinkers, a parody on the four ages of man. The exaggerated figure types capture Daumier’s characteristic humor and convey his sad message about the horrors of alcoholism. The greenish palette may well be an allusion to the notorious alcoholic drink absinthe.

The Letters of Vincent van Gogh

To Emile Bernard. Saint-Rémy, on or about Tuesday, 8 October 1889.

My dear friend Bernard,

The other day my brother wrote to me that you were going to come to see my canvases; so I know that you’re back, and I’m very pleased that you thought of going to see what I’ve done.

For my part, I’m extremely curious to know what you’ve brought back from Pont-Aven.

I hardly have a head for writing, but I feel a great emptiness in no longer being at all up to date with what Gauguin, you and others are doing. But I really must have patience. I have another dozen studies here, which will probably be more to your taste than the ones from this summer that my brother will have shown you.

Among these studies there’s an entrance to a quarry, pale lilac rocks in reddish earth, as in certain Japanese drawings. In terms of design and the division of colour into large planes, it’s quite closely related to what you’re doing in Pont-Aven.

I had more control over myself in these latest studies, because my state of health had firmed up. So there’s also a no. 30 canvas with broken lilac ploughed fields and a background of mountains that go all the way up the canvas; so nothing but rough ground and rocks, with a thistle and dry grass in a corner, and a little violet and yellow man. That will prove, I hope, that I haven’t yet gone soft.

Dear God, this is a pretty awful little part of the world, everything’s hard to do here, to disentangle its intimate character, and so that it’s not something vaguely true, but the true soil of Provence. So to achieve that, you have to toil hard. And so it naturally becomes a little abstract. Because it will be a question of giving strength and brilliance to the sun and the blue sky, and to the scorched and often so melancholy fields their delicate scent of thyme. The olive trees down here, my good fellow, they’d suit your book; I haven’t been fortunate this year in making a success of them, but I’ll go back to it, that’s my intention. It’s silver against orangeish or purplish earth, under the great blue sky. Well now, I’ve seen some by certain painters, and by myself, which didn’t render the thing at all. Those silver greys are like Corot first of all, and that, above all, hasn’t been done yet — while several artists have been successful with apple trees, for example, and willows.

So there are relatively few paintings of vineyards, which are nevertheless of such changing beauty. So there’s still plenty for me to fiddle around with here.

Look here, what I very much regret not having seen at the Exhibition is a series of houses of all the nations; I think it was Garnier or Viollet-le-Duc who organized it. Well, could you, who will have seen it, give me an idea, and especially a croquis with the colour of the primitive Egyptian house? It must be very simple, a square block, I believe, on a terrace — but I’d like to know the colouring too. I was reading in an article that it was blue, red and yellow.

Did you pay attention to it? Please inform me without fail! And it mustn’t be confused with the Persian or the Moroccan; there must be some that are more or less it, but not it.

Anyway, for me the most wonderful thing that I know in terms of architecture is the cottage with a mossy thatched roof, with its blackened hearth. So I’m very fussy. I saw a croquis of ancient Mexican houses in an illustrated magazine; that, too, seemed primitive and really beautiful. Ah, if only one knew the things of those days, and if one could paint the people of those days who lived in them — it would be as beautiful as Millet. Anyway, what we do know that’s solid these days, then, is Millet; I’m not talking about colour — but as character, as something significant, as something in which one has solid faith.

Now, about your service; will you go? I hope you’ll go to see my canvases again when I send the studies of autumn, in November. And if possible let me know what you’ve brought back from Brittany, because I’d really like to know what you yourself believe to be your best things. So I’ll write again soon.

I’m working on a large canvas of a ravine; it’s a subject just like the study with a yellow tree that I still have from you, two bases of extremely solid rocks, between which a trickle of water flows, a third mountain that closes off the ravine. These motifs certainly have a beautiful melancholy, and it’s enjoyable to work in really wild sites where you have to bury your easel in the stones so that the wind doesn’t send everything flying to the ground.

Handshake.

Yours truly,

Vincent