ArtsVanGogh.com

Vincent van Gogh 1853-1890

Vincent van Gogh - Two Peasant Women Digging in Field with Snow 1890

/127 Two Peasant Women Digging in Field with Snow.jpg) Two Peasant Women Digging in Field with Snow |

Morning: Going to Work

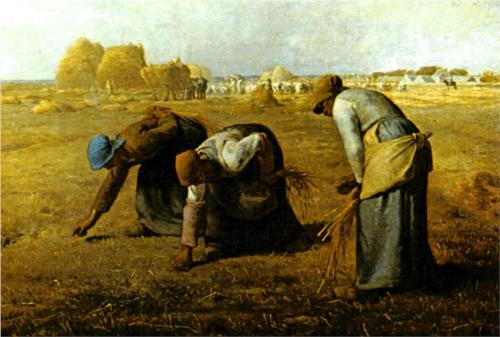

Jean-Francois Millet

1858-1860

Van Gogh used the women from Millet's The Gleaners as inspiration for this painting of women digging in the frozen snow. Unlike the others, this work is not a literal translation of the original painting. The setting sun casts a warm glow over the fields of snow. The cool colors of the field contrast to the red in the sun and sky.

From Foundation E.G. Bührle, Zurich:

In the hospital of Saint-Rémy, which van Gogh was confined to from 1889 until May 1890, the

dichotomy of his tragic life becomes apparent. He is not always allowed to paint in the garden and the environs of the hospital. When he is ill he has only the view

from his barred cell on to the ascending field, which he paints again and again in different lights and seasons. He has no human models either, since he finds repellent

the inmates dully lounging about. He longs for healthy working peasants. The reproductions of Millet, sent by Theo, make up somewhat for this. He converts them into

paintings, and they become for him "recollections of the north" or "recollections of Brabant", as he almost tenderly expresses it to his mother.

"The Weeders" is truly a recollection, since even at Nuenen he had struggled to paint a picture of a woman gathering roots in the snow. Perhaps these recollections were

unleashed by a snowfall at Christmastime in Saint-Rémy, of which he reports to Theo: "During my illness, white snow fell, I got up in the night to look at the countryside.

Never before did the landscape seem so moving and sensitive". And so the dazzling glare of the south becomes the glistening snow of the north with the bending peasant women

in the snow-covered field in front of the thatched hovels, behind which in a turbulent sky the yellowish-red sun is setting: a recollection and also a picture expressing

nostalgia for the north.

The Letters of Vincent van Gogh

To Theo van Gogh. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, on or about Tuesday, 19 November 1889.

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter, and am very glad that you write that Jo is staying well. The great event is nearing now, I think of you both very often. For you, when you write about seeing so many paintings that you would wish not to see any for a while, this clearly proves that you’ve had too many business worries. And then – yes there’s something in life other than paintings, and this something else one neglects and nature seems to avenge itself then, and besides, fate is bent on thwarting us. I think that in these circumstances one must keep to the paintings as much as duty demands but no more. As for the Vingtistes, here’s what I’d like to exhibit:

1 and 2 the two pendants of sunflowers

3 The ivy, upright

4 Orchard in blossom (the one Tanguy’s

exhibiting at the moment, with poplars crossing the canvas)

5 The red vineyard

6 Wheatfield, rising sun, which I’m working

on at the moment.

Gauguin wrote me a very kind letter and speaks animatedly of De Haan and of their rough-and-ready life at the seaside.

Bernard also wrote to me, complaining about a heap of things while resigning himself like the good boy he is, but not happy at all; with all his talent, all his work, all his sobriety, it appears that home is often a hell for him.

Isaäcson’s letter gives me great pleasure, I enclose my reply which you will read – the ideas are beginning to link together a little more calmly, but as you’ll see from it I don’t know if I should continue to paint or leave painting alone.

If I continue, certainly I’m in agreement with you that perhaps it’s better to attack things with simplicity than to seek abstractions. And I’m not an admirer of Gauguin’s Christ in the Garden of Olives for example, a croquis of which he sent me. Then as for Bernard’s, he promises me a photograph of it, I don’t know, but I fear that his biblical compositions will make me wish for something else. Lately I’ve seen women picking and gathering olives, no way for me to get a model, so I didn’t do anything about it. However now isn’t the moment to ask me to approve of friend G’s composition – and friend Bernard has probably never seen an olive tree. Now he therefore avoids conceiving the least idea of the possible and of the reality of things, and that isn’t the way to synthesize. No, never have I got involved in their Biblical interpretations. I said that Rembrandt and Delacroix had done this admirably, that I liked that even better than the primitives, but then stop. I don’t want to begin on that chapter again. If I remain here I wouldn’t try to paint a Christ in the Garden of Olives, but in fact the olive picking as it’s still seen today, and then giving the correct proportions of the human figure in it, that would perhaps make people think of it all the same. Before I’ve done more serious studies than I have up to now I don’t have the right to get involved in this. And then the Pre-Raphaelites went a long way in that category of ideas. When Millais painted his Light of the World it was serious in another way. Really, there’s no comparison. Not to mention Holman Hunt and others, Pinwell and Rossetti.

And then here there’s Puvis de Chavannes. Now I’ll tell you that I’ve been to Arles and I saw Mr Salles, who handed me the rest of the money you sent him and the rest of what I’d handed over to him, that is, 72 francs. However, only around twenty francs remain in the cash-box with Mr Peyron at the moment, since down there I stocked myself up with colours and paid for the room where the furniture &c. is. Stayed there for 2 days, not yet knowing what to do next, it’s good to show oneself there from time to time so that the same story doesn’t start again with the people. At present no one there is hostile to me as far as I can tell, on the contrary, they were very friendly, and even gave me a warm welcome. And if I stayed in the area, little by little I’d have a chance to acclimatize myself, which isn’t easy for strangers and would have its uses for painting there. But first we’ll see a little if this journey might provoke another crisis. I almost dare hope not.

It’s often cold here too, however we’re a little more sheltered from the mistral by the mountains. And between times I keep working. I have several things to send you with the canvas for the Vingtistes. I’m waiting for that one to be dry.

If I’d known in time that there were trains from here to Paris at only 25 francs I would certainly have come. It’s only on going to Arles that I found this out, and it’s because of the expense that I haven’t done it – at the moment it would seem to me that in springtime it would however be good to come in any event to see the people and things of the north again. For this life here is terribly numbing, and in the long run I’d lose my energy. I had hardly dared hope that I would still be as well as is the case.

However, everything depends on whether this suits you or not, and I think it’s wise not to rush things. Perhaps by waiting a little we won’t even have need of the doctor at Auvers or the Pissarros.

If my health remains stable, then if while I’m working I again start to try to sell, exhibit, make exchanges, perhaps there’ll be some progress so as to be less of a burden to you on the one hand and to regain a little more zest on the other. For I don’t hide from you the fact that my stay here is very tiring on account of its monotony, and because the society of all these unfortunates, who do absolutely nothing, gets on one’s nerves.

But what can one do, one can’t have pretensions in my case, I already have too many as it is.

Gauguin says that they get models easily. That’s what I lack most here.

Bernard speaks to me of an exchange, you’re quite free to deal with this with him if he wishes and speaks to you about it. I’d really like that, besides the portrait of his grandmother, you should have a good thing of his. It appears he fancies the Berceuse.

I think that the 6 paintings for the Vingtistes will make an ensemble like this, the wheatfield will make a very good pendant to the orchard.

I’m dropping a line to Mr Maus to give him titles, as he asks in his letter.

Now, warm regards to Jo, and good handshake.

You must read the letter to Isaäcson, it complements this one. More soon.

Ever yours,

Vincent